Table of Contents

More Is More Complex (MIMC)

Variants and Alternative Names

- Less is more

Context

Principle Statement

More is more complex.

Description

Having more lines of code, methods, classes, packages, executables, libraries etc. always means also to have more complexity (which is bad). This means that given the complexity of the problem is fixed, a suitable compromise for the number of methods, classes, etc. has to be found. Reducing the number of statements per method typically results in the introduction of further methods. Reducing the number of methods per class can be achieved by dividing the class into several smaller classes, etc.

There is both: too large modules (i.e. undermodularization) and too small modules (i.e. overmodularization). Either there is too much complexity in a module (MIMC applied to one module) or there is too much complexity between the modules (MIMC applied to the number of modules).

Note that it is actually not the number of lines, methods, classes, etc. that is relevant but the effective number of items that have to be kept in mind for the purpose of understanding. So reducing the number of lines by placing several statements in one line does not help. Neither the introduction of an additional obvious private method exceeding the limit will do any harm. MIMC is just a rule of thumb stating that the introduction of further modules (and the like) usually has a higher complexity as a drawback.

For documentation it simply states that fewer documentation is better.

Rationale

The capabilities of the human mind are certainly limited. If it is necessary to keep a large amount of modules or lines of code in mind, it is difficult to understand. Furthermore if a module is large, it takes a long time to read (and thus to comprehend). And if there are many modules, looking for a particular module takes a long time. And the longer the searching process takes, the more one will have forgotten what has been read previously. This results in worse readability, understandability and thus maintainability.

Regarding documentation it is evident that smaller amounts of documentation are read faster.

Strategies

- Avoid many modules

- Merge several modules into one

- Don't introduce a new module but put the functionality into another module

- Avoid big modules

- Divide large modules into several smaller ones

- Introduce new modules to group related functionality. A Parameter Object is a typical example for this.

Caveats

- Note that Miller's Law is often cited in this context but it is doubtful if and to what extend it applies.

- Note that this principle is contrary to itself. Given a desired functionality a certain level of complexity in inevitable. This leads in the extremes either to a large amount of small classes or a large amount of code in a fewer class. The same applies on other levels like number and size of methods, etc. So there is always a tradeoff between MIMC and itself applied to different aspects of the software system.

- Furthermore note that having more classes can be regarded better than having too large classes. See Add More Classes.

- Having no documentation is best with respect to MIMC. But of course there are contrary principles.

See also section contrary principles.

Origin

The phrase “more is more complex” is new but can be regarded trivially intuitive to every developer. There is also some research concerning certain aspects of MIMC. See section evidence.

Evidence

Examined: There is some research relating module size to certain quality attributes like maintenance cost, error density, etc. Basili and Perricone studied maintenance data of Fortran programs for aerospace applications 1). They found that the smaller modules had a higher error density than the larger ones. At first this seems to contradict MIMC. But assuming there is a certain essential complexity of the problem, this complexity has to be implemented somehow. Either this leads to a few large modules or many smaller ones. In the latter case the complexity is in the relationships and interactions between the modules instead of the modules themselves. So too small modules result in more modules and more complex communication among them. Other studies seem to confirm this2).

This phenomenon that the defect density is high for small modules but also rises for large modules is called the “Goldilocks Conjecture”. As a result there is an optimal module size which is neither too small, nor too big. Several publications claim to have found this optimal module size3). Depending on the programming language used, these values typically are claimed to be a few hundred lines of code. Note that most of these studies are in the context of procedural programming.

This sounds intuitive but the Goldilocks Conjecture is disputed. Some point out that the negative correlation between defect density and size is just a mathematical artifact4)5) and that there are also other methodological problems with these studies6). There is also data which is not explainable by defect models based on the Goldilocks Conjecture7).

The relationship between module size and defect proneness is complex and not clear. Furthermore modularization is not only a task in terms of module size. The more interesting aspect is how to assign responsibilities to modules. So apart from module size there are many other aspects influencing modularization (see especially MP, LC, and HC) which makes it hard to isolate the pure effect of size.

This is an important research question but as MIMC is just a qualitative rule of thumb (just as the other principles are). So the principle can be deemed helpful despite the Goldilocks Conjecture being disputed.

As a specific aspect of MIMC, complexity through deep inheritance relations is known to reduce effectiveness and efficiency of maintenance. There are controlled experiments showing this8)9). On the other hand these results are limited as there may be many factors which are neglected by the experiment. Most notably in these experiments maintenance tasks where carried out on systems with artificially constructed inheritance hierarchies. It is undisputed hat there are good ways and bad ways of using inheritance. And it is doubtful that there are several equally good solutions for the same problem only differing in the depth of inheritance. So there is some evidence but no “proof” that deep inheritance hampers maintenance.

Questioned: The Goldilocks Conjecture, which can be seen as an aspect of MIMC, is disputed. See above.

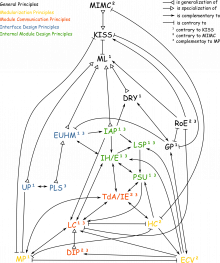

Relations to Other Principles

Generalizations

- Keep It Simple Stupid (KISS): MIMC states that having more modules, etc. leads to more complexity. KISS on the other hand is about the avoidance of every form of complexity.

Specializations

Contrary Principles

Note that many principles are contrary to MIMC as they favor the introduction of additional modules. This means that it is worthwhile to consider MIMC when considering one of those. Nevertheless this does not mean that this is true the other way around. When considering MIMC, one wouldn't want to consider all principles that have complexity as a disadvantage. So here are those needing consideration:

- More Is More Complex (MIMC): Changing a design to adhere to the MIMC principle may always lead to more complexity concerning another aspect of the system. For example reducing the amount of code in a large method is typically achieved by the introduction of further methods. So there is always a tradeoff between this principle and itself.

- High Cohesion (HC): Not introducing further modules typically leads to a lower cohesion.

- Add More Classes: While MIMC is a very general principle that applies to virtually everything, it may be regarded better to have more classes than bigger classes.

- More Stakeholders, More Details (MSMD): The more stakeholders there are, the more documentation is needed.

- Navigation Avoidance Principle (NAP): When trying to minimize documentation try not to create the need for navigation.

Complementary Principles

- Miller's Law: This is the law about a conceptual limit often cited as a (user interface) design rule.

- Document the Hard Stuff (DHS): When trying to minimize documentation DHS tells you what you should document and what you can leave out.

- Don't Repeat Yourself (DRY): Eliminating duplication is a way to reduce complexity.

Principle Collections

Examples

Description Status

Further Reading

Discussion

Discuss this wiki article and the principle on the corresponding talk page.